A Short Story of Art

Once, in the early age of modernity, there was a civilization that invented the art as a way of reflecting the world. Art was understood as an intellectual activity expressed through painting and sculpture by specially gifted individuals named artists. In order to show works of art, first the galleries and exhibitions had to be invented. Then, the art market and the museums emerged and a notion of art spread to all epochs and civilizations.

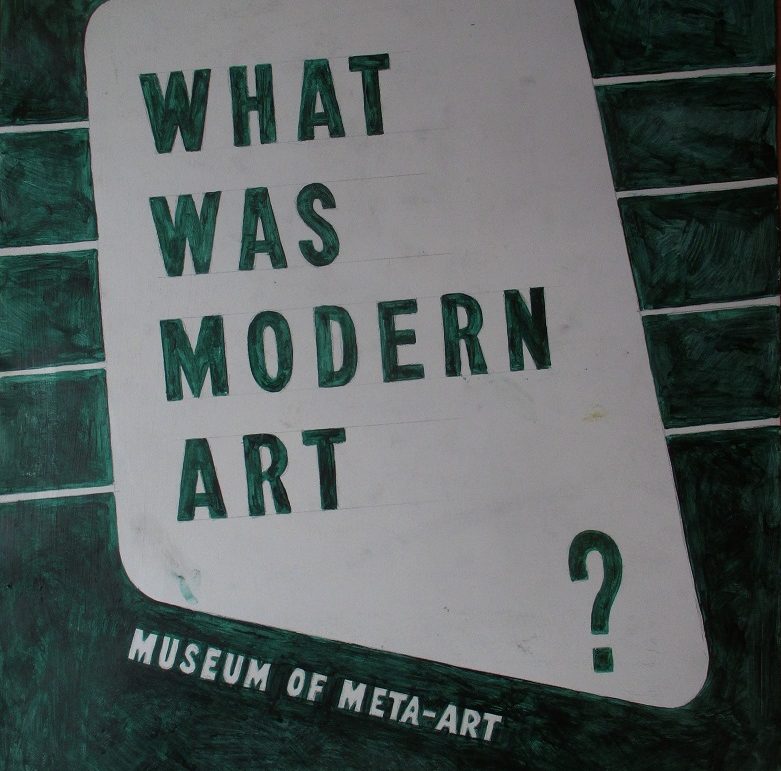

The exhibition in front of us is a journey through various ways in which all those achievements of what once was modernity: museums, exhibitions, art history, works of art and art itself, could be observed and interpreted today.

The exhibition The Making of Modern Art situated at the ground floor of the collection building, developed in cooperation with the Museum of American Art, Berlin. It combines modern master pieces from the Van Abbe collection, like Mondrian, Picasso, Sol LeWitt, Kandinsky and Leger, with an experimental story, which tells the ‘making of’ of the classical canon of modern art. Through a series of specially designed ‘atmosphere rooms’, the exhibition addresses the role of museums, and shows how exceptional collectors and influential exhibitions contributed to the formation of the modern canon, which also lies at the foundation of the Van Abbemuseum collection. Throughout the display the visitor will be offered a different perspective in each room which will focus on one aspect of the logic and establishment of the story of modern art. The designs of the rooms thereby themselves introduce a physical environment which helps the viewer to experience known works of modern art in a very different way.

Room 1 A Story of Art Museums

Belvedere Romanum

When in the beginning of the 16th century Pope Julius II placed several statues from the distant past in the Vatican garden Belvedere because of their beauty, and opened it to the public, it was not only the birth of antiquity, but modernity as well, while the permanent display of statues became the first museum.

Beautiful View

There was a certain pope that was very fond of statues from the ancient times. One day he decided to have a garden on the nearby hill where he would go to rest and enjoy the statues. The garden in which he grew flowers of the most fragrant smell and fruits of the most delicious flavor was named Belvedere. In short, nothing on earth could exceed it. The first statue he brought to the garden was the one of the Greek god Apollo. This was considered to be the most beautiful statue of all times. After not too long, he learned about the discovery of the statue of the ancient priest Laocoon and his two sons strangled by the giant serpents.

In a short time this became the most admired statue in the entire world. The pope managed to acquire a few more statues and place them in the garden. Whenever he had time the pope would visit his beautiful garden. He would sit under the orange tree and enjoy the sight of the ancient marbles. While contemplating about the glorious times past, he believed that it was the Antiquity that was coming back alive here in this garden. But the pope was not aware that in his passionate search for Antiquity he has in fact discovered Modernity as well. From the Tales of the Artisans

Louvre Museum – Paris

Almost three centuries later, during the French revolution, the statues from the antiquity were exhibited in the Louvre together with the collection of paintings that represented the modernity, while between them were placed the remains of medieval France preserved in the Museum of Monuments. This is how for the first time, through the museum display, emerged a three part structure: antiquity-middle ages-modernity, that became the backbone of (art)history based on chronology and uniqueness.

Some time ago there dwelt some a mighty and a merciful emperor who ordained such a law that a magnificent collection of paintings should be hanged on the walls of his palace according to the rules of symmetry. For many years this was considered to be the most reasonable and most beautiful way for displaying the paintings.

One day some of the court painters came to the emperor begging to borrow two of the paintings from the collection that were made by two different painters. They wanted to show the paintings to the students who were studying the art of painting. The emperor was very generous and gave them permission to do so. When they selected the paintings they took them to the classroom and hang them next to each other on a wall in front of the students. In this way the students were able to study the similarity and differences between the paintings and recognize a specific style characteristic for each of the two painters. Now the rule for hanging was not determined by symmetry but by the distinct way of painting characteristic for each painter.

Many years later, during the Great Revolution, the rules for hanging the paintings were changed again. The new revolutionary authorities ordered that all the paintings should be exhibited not according to their properties but by the nationality of each painter. This rule became adopted by most of the museums and lasted for many decades. Then came the young director of a new museum on the other side of the ocean who instead of nationality introduced another rule for hanging the paintings. He decided that the paintings should be grouped and hanged together primarily according to the movements they belonged to. In spite some resistance this new rule gradually gained ground and it is today adopted everywhere in the world, and it will last until some new rule for hanging is introduced. Perhaps symmetry…

Landesmuseum – Hannover

The art museums that opened later followed this structure while displaying artifacts in the same way regardless of the epoch until 1920es when, in the Landesmuseum in Hanover, Alexander Dorner introduced the idea that art of each epoch should be displayed in a specially designed room named the “Atmosphere Room”.

. Although the connection between the Museum and Art History was well established, throughout the 19th and early 20th century the display narrative of the museums was governed by other criteria like symmetry, the paintings’ size, subject matter or the collection from whence they came rather than by chronology and evolution.

The design of the museum displays was uniform regardless of the period, epoch or style, and that would give an impression of the timelessness of the Museum itself. When we go to the Museum we see the past, arranged as History, which is fixed and unchangeable. Of course, this was just a ‘temporary timelessness,’ since the technology, design, and aesthetic of museum displays were changing all the time. And thus the picture of the past kept changing as well.

The Provinzial-Museum in Hanover (later Landesmuseum) was one such place at the time young Alexander Dorner became its director. Soon after, realizing the necessity of a radical change of the museum’s display, he came up with the idea to show the development of art as a chain of specially designed ‘Atmosphere Rooms.’ He adopted not only chronology, but also the evolutionary principle, as the foundation for the museum’s display narrative. Each epoch, period or style would be confined in its own specially colored and designed rooms, exhibiting not only the artifacts, but immersing the visitor in a complete visual experience. Walking from one room to another, following the progressive timeline, a visitor would be able to see and experience the entire history of art as a progression of styles from the beginning of civilization to the present day. The most famous room became one devoted to abstract art designed by Constructivist artist and designer El Lissitzky. Since Lissitzky had designed a special room for abstract art at the 1926 International Kunstausstellung, Dorner thought to ask him to do something similar now as a permanent installation at the Hanover museum.

The result of this idea was the Kabinett der Abstrakten (Abstract Cabinet), opened in 1928. Among the various photos of the Kabinett we can recognize works of Picasso, Leger, Moholy-Nagy, Mondrian, Archipenko, Schlemmer, Baumeister, Van Doesburg , Marcoussis and El Lissitzky. There are indications that some of the works from Malevich’s 1927 Berlin exhibition** were exhibited as well. Those might be the works that Alfred Barr got from Dorner, later in 1935, for the exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art , which remains on permanent display at the MoMA until today.

Museum of Modern Art – New York

A few years later in New York, in the newly opened Museum of Modern Art , Alfred Barr suggested that the story of modern art should be told through the developments of the international avant-guard movements. This concept of art, based on internationalism and individualism, became adopted by the entire art world.

Ethnographer and the Natives

Once upon a time, there lived an adventurous young man. Being an explorer and ethnographer at heart, he longed to travel and make great discoveries. Then it happened one day that he heard a tale about some curious developments among the natives

of the Old World. A new style in the making and decorating of art objects, it was said, had been spreading among the craftsmen of various tribes. The movement was already dying out, however, and soon it would slip into oblivion. Intrigued, the explorer immediately organized a series of expeditions across the ocean. He visited all the important places, collected paintings and other exotic objects from the natives and recorded the stories they told. Impressed with what he saw and heard, he brought back many artifacts and decided to establish an ethnographic museum, naming it the Museum of Modern Art.

Soon afterward, the explorer organized an exhibition of the two most unusual styles, which were known as Cubism and Abstract Art. The exhibition was a great success, and it became the standard for the museum’s permanent display. It was also widely imitated by the museums of modern art that came after.

The story told through this museum exhibit became known as the History of Modern Art, and this too was accepted throughout the entire world. After the Great War, even the natives of the Old World adopted the story as their own. In time, they went so far as to embrace this story as their own authentic and dominant myth. And so it came to

be that it has been retold and reenacted in countless annual and biannual

celebrations and rituals ever since. From the Tales of the Artisans

*******

This story of the development of art museums in the West is presented here as a beautiful panorama view from the “Orient” toward the exotic “Occident”.

Room 1a The Invention of the Art Scene

Uffizi Gallery – Firenze

One of the origins of the art scene as we know it today could be traced to Vasari and his 1550 book “Lives of Painters, Sculptors and Architects”, beginning with the earliest masters Cimabue and Giotto and culminating with Leonardo, Raphael and Michelangelo as distinct individual characters. In addition to this first history of art, Vasari could be credited for the introduction of gallery (Uffizi) as a special space where a number of paintings could be put on display, and as one of the originators of the academies, specialized schools to study painting and sculpture.

Academie – France

A century later, a painter Le Brun, expanded this idea and initiated the establishment of Art Academy as a school, but also as an association of painters and sculptors under the State Council of Louis XIV. On January 28, 1648, the Council issued a decree in which painting and sculpture are defined as liberal arts and thus removed from the guild system. From then on, painting was not perceived only as a craftsmanship, but as an intellect activity similar to poetry. In 1667, Le Brun and the Prime minister Colbert suggested that members of the Academy present their works in the Salon Carré in a non-commercial display(exposition). It became a regular event called “The Salon” and represents the invention of the temporary art exhibition.

Art Market – Lowlands

At that time in the neighboring Lowlands, with the emergence of the bourgeoisie, it became apparent that some kind of paintings like landscapes, still life, and genre paintings could be used not only as a house decoration but also as an investment. This led to the appearance of the specialized shops for selling paintings which is the origin of the commercial galleries and the art market.

Room 2 A Story of De-artization

After the French Revolution many of the sacred objects were taken from the churches and brought to the Musee Central (Louvre) and exhibited not as religious objects but as works of art. This process known as de-sacralization took place in many museums throughout the 19th century. Since then, all the works in the art museums that were produced before the establishment of the museum had two layers of meaning, two different roles in two different stories (sacred object in a religious story and work of art in art history), while the works produced after the establishment of the museum have only one layer of meaning – they are just works of art.

Some of the samples exhibited here are considered today to be works of art, while there are other that were at some point works of art but are now treated as historical artifacts. Regardless of their current status, they are all exhibited here as art artifacts primarily because of some interesting story or an event associated with each of them. This process of turning a work of art into a document about art, (art artifact), Walter Benjamin named de-artization, and it seems it was introduced for the first time in the MSUM in Ljubljana on the art work, a painting “Lenin and Coca-Cola” by Alexander Kosolapov.

Lenin Coca-Cola by Alexander Kosolapov and Related Artefacts – painting, oil on canvas, 1980 – objects, publications, film footage, related to Lenin and to Coca-Cola various dimensions and materials, 1917–2011

With the establishment the first art museum more than 200 years ago, all the artefacts from the past included in museum collections were transformed into works of art. Even today those artefacts have at least two layers of meaning: one is defined by their original purpose (sacred paintings, for example) and the other has been acquired in the art museum in their being declared art. Art museums, in which artworks were organized chronologically and by national schools, played a decisive role in establishing the History of Art as it was structured on the same principles. Ever since the first museum, all the newly produced artefacts included in art museums are immediately conceived as works of art. In other words all those paintings, sculptures, objects, photographs, collages, ready-mades, installations, performances, et cetera that emerged within the field of art museums and art history have claimed one layer of symbolic meaning: to be understood, interpreted, and exhibited only as art.

Since it became apparent in recent years that art is not some universal category but basically an invention of Western (European) culture, a “child” of the Enlightenment decisively shaped by Romanticism, it might be worthwhile to contemplate other possibilities for interpreting and exhibiting artefacts conceived and treated as art up until now. One way of doing this is to gradually detach from the notion of art and to try to look at an artwork as a human-made specimen, an artefact of a certain state of mind or cultural/political milieu. This approach should not be that of a passionate believer and admirer of art, but diagnostic, with almost the cold approach of an ethnographer. In order to fully establish this “dispassionate” position, some of the existing art museums would have to gradually transform into anthropological museums about art – new kinds of museums that would enable the deartization of existing works of art into non-art artefacts in the way the desacralization of religious paintings and objects change their meanings by moving them from churches into the art museums. Until this (deartization) happens, perhaps it might be still possible to apply this approach to individual works of art within art museum displays we have here.

This work of art is a painting by Alexander Kosolapov, Lenin Coca-Cola (1980), from the collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Ljubljana. Its iconography is recognizable since it combines two well-known and opposing icons in twentieth-century mass-culture. One is a portrait of Lenin (Vladimir Ilich Ulyanov) leader of the first socialist revolution out of which the Union of Soviet Socialistic Republics (USSR) emerged in 1917, a country that helped shape world history in the last century until its demise in 1991. Despite his early death in 1923, Lenin‘s image, which often appearing on red banners , has become one of the most recognizable symbols of the international communist movement. Another worldwide known symbol is the logo for Coca-Cola, possibly the most popular soft drink today. First introduced in 1886 in the United States, it is now sold in more than 200 countries, and its white letters on a red background have become a symbol of globalism and consumerism as the ultimate achievement of liberal capitalism.

Together with the painting, exhibited here primarily as an artefact, are various randomly selected objects and film-clips from mass-culture, related either to Lenin or Coca-Cola, exhibited also as artefacts. These artefacts should offer some information about the broader political and cultural context necessary to understand the iconography within Lenin Coca-Cola wherein the symbols, contradiction between them, and a sense of irony merge into a single image.

There is no way to predict how long Lenin and the meaning of his image will be remembered, nor even that of Coca-Cola as a drink and its logo. But we can be almost certain that on their slow journey into oblivion the meaning of these two symbols will transform in a way we cannot anticipate. When that happens, the original meaning of this painting will disappear, and if it physically survives and finds a new purpose, the painting will acquire a completely new interpretation. By exhibiting this painting together with other related artefacts, we might prolong the preservation of its original meaning – but only up to the point. In the long run there is a good chance that even this attempt will have limited and unpredictable future.

Walter Benjamin, Berlin, 2011

————————————————————————–

Walter Benjamin is art theorist and philosopher who in ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ (1936) addressed issues of originality and reproduction. Many years after his tragic death in 1940, he reappeared in public for the first time in 1986 with the lecture Mondrian ‘63 –‘96 in Cankarjev dom in Ljubljana. Since then he also published several articles and gave a few interviews on museums and art history. His most recent appearance was for the lecture The Unmaking of Art in 2011 at the Times Museum in Guangzhou. In recent years Benjamin became closely associated with the Museum of American Art in Berlin.

Mondrian – Original and Copy

In front of us are two (abstract) paintings. One is the original 1930 Composition by Piet Mondrian from the Van Abbemuseum collection, and next to it is its recent copy. Together they allow us to experience the full force of the combination original and copy. They pose interesting questions, for instance: if the original is an abstract painting, is its copy also an abstract painting?

In 2002, Walter Benjamin made the following remarks on the matter in the article On Copy: “Is a copy of an abstract painting, an abstract painting? In the copy we still see the original, thus it should be an abstract painting; on the other hand, being a faithful reproduction of another painting (object), it should be also a realistic painting. This ambiguity shows how a simple copy of an abstract painting could transform something “known” into something “unknown”, turning the entire modernistic worldview upside-down, and revealing that our idyllic backyard could be a minefield, too.”

Madonna and Child

Once this sculpture Madonna and Child was a sacred object worshiped in a church. Being desacralized at some point, it was turned into a work of art and it is today in the Eindhoven Museum collection. This statue is exhibited here neither as a religious object nor as a work of art, but as an artifact that remembers the event of desacralization. To remember this process we also, for the time being, need to stop to consider it as artwork. but as a “cultural artifact” with possible different meanings. So with the help of deartization we can make desacralization visible.

Sol LeWitt, Superflex and Alexander Dorner

In 2010 the Danish artists collective Superflex realised Free Sol LeWitt. For this project they turned one museum room into a workshop to reproduce Sol LeWitt’s Untitled (Wall Structure) (1972) from the Van Abbemuseum’s collection. The copies distributed for free to the public through a lottery system. With this gesture Superflex took Sol LeWitt’s statement on his work to hearth:

In conceptual art the idea or concept is the most important […] the execution is a perfunctory affair. The idea becomes a machine that makes the art.

Sol LeWitt, Paragraphs on Conceptual Art, 1967

Superflex’s action also responds to the museum’s function to make artwork accessible to the public. With Free Sol LeWitt Superflex did this in a radical way and made an artwork freely available to the public.

Even if unitended the project also recalls a remarkable exhibition made by museum director Alexander Dorner Facsimile and Copy (1929), in Provinzialmuseum (now Landesmuseum), Hannover. In this exhibition paintings were exhibited next to high-quality colour photo reproductions, inviting the public to decide which is which. In 2011 Alexander Dorner mysteriously returned and exhibited the original Sol LeWitt Untitled (Wall Structure) (1972) next to a Superflex copy in Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA) under the title: Original and Facsimile.

Picasso – Portrait

Ben Nicholson – Government Defines Art

If Ben Nicholson’s, White Relief, (1936) from the Van Abbemuseum collection, would be send to United States in 1936, there is a good change that the US customs would declare that it is not a work art. This was the curious fate of a similar work of Nicholson, which was to be exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA). Another case of deartization.

The cover of this 1936 MoMA Bulletin presents a photograph from the US customs showing works of modern art to be presented at the exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art. However, 19 sculptures out of 150 were refused duty-free entry under the Treasury Department rule that required sculpture – but not paintings – to be “imitations of natural objects…chiefly the human form.”

This strict interpretation forced the MoMA to delay the opening of the exhibition for a week and to post a $100,000 bond to release the works. The incident prompted Museum president A. Conger Goodyear to rally museums around the country in a letter-writing campaign to have the US customs laws amended “to permit recognized museums to decide what art is.”

The issue in which the Museum of Modern Art and all similar institutions are really interested is whether the government is to determine by law what is art. In this instance there is no question as to the ‘moral’ character of the objects under consideration. They are denied admission, duty free, on the sole ground that they do not completely meet the requirements established by the existing law and court decisions for ‘works of art.’ The judgment of acknowledged experts is given no weight or consideration.

The excluded works:

Arp, Human Concretion

Giacometti, Standing Figure, Head-Landscape, Project for a city square,

Laurens, Bottle of Rum, Head, Guitar

Vantongerloo, Construction Within a Sphere, Construction of Volume Relations, Construction of Volume Relations [2]

Duchamp-Villon, The Lovers [2], The Horse

Gonzales, Head

Boccioni [misspelled as Doccioni], Development of a Bottle in Space, Continuity of Form in Space

Moore, Two Forms

Nicholson, Relief

Miro, Construction

Malevich – Bourgeois Art

On this 1931 photograph we can see an installation view of an exhibition titled Bourgeoisie Art in Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia. The exhibition was made during the socialist rule in the former Soviet Union. We can recognize paintings by Tatlin, but also Malevich’s The Haymaking (1929). Above the painting there is a large letter pane; almost the same size as the painting saying: “On this painting it is not possible to recognize an objective, creative method, since, as an example of bourgeois art, it is thoroughly individualistic.” he painting is thus explicitly labeled as ‘bourgeois and individualistic art’ and considered in opposition with the collective nature of socialism.

In the Soviet Union ‘bourgeois’ was entirely dismissive term, implicating that what was on show was not really art, but the impure art of the bourgeois world. Thus this is another case of deartization, as here again an artwork is turned into an artifact. These exhibitions marked the last moment when the famed artists of the avant-garde were visible with the Soviet Union. After this kind of exhibitions they were slowly removed from the gallery walls and disappeared from public life, not to be seen for many decades.

Guenther Brendel – Socialistic Realism

Aufbau des Stadtzentrums Berlin (Construction of Central Berlin) (1961), is painted by Günther Brendel, an artist celebrated in the former German Democratic Republic. In 1976 he even was commemorated with the exclusive Banner of Labor. Sadly for Brendel his art today is less valued. Placed in the historical museum, it is considered part of the tradition called Social Realism and presents another interesting case of deartization.

At the time October Revolution (1917) in Russia, avant-garde artists identified with it and enthusiastically took part. They translated the political experiment of socialism into radical artistic experiment, known as Constructivism. However, after a few years the Soviet Union moved away from this radical and abstract art, and eventually removed all modern art from the museums. Instead, they introduced Social Realism as the proper art and, after the war, made it the norm in all countries part of the Soviet block. After the fall of the Berlin Wall and demise of socialism, this art, rejected by the West as it lacked the spirit of innovation typical for modern art, was mostly removed from art museums. Such is also the fate of this painting of Brendel, which you see here today.

Otto Arndts – Ostmark 1939

Otto Arndts’ painting Ostmark from 1939 was exhibited at the 1940 at the Grosse Deutsche Kunstausstellung (Great German Art Exhibitions) in Haus der Deutsche Kunst (Hous of German Art) in Munich and was acquired by Adolf Hitler for his private collection. The Great German Art Exhibition was an annual exhibition organized under the National Socialist rule since 1937 to promote ‘real’ German art. This art stood in strong opposition to modern art, which was made in international networks of artists. However, after World War II paintings like Ostmark lost their importance as art. Now they are kept in the Historical Museum and became historical artifact. It is the irony of history that the art of the National Socialist regime, which tried to deartizice modern art, today is dearticized.

Beckman – Degenerate “Art”

During the fascist rule of National Socialism in Germany in the 1930s and 1940s, a decision was made that the modern art should be removed from all museums in Germany. However, before being disposed one way or another, in 1937 modern art was shown throughout the country in a mocking and disparaging way as ‘Bolshevik’ “Jewish”, and “ insane”. In the traveling exhibition titled Entartete “Kunst” (Degenerate “Art”) everybody had a chance to learn about this “art” before it was removed from the public eyes. After the defeat of National Socialism modern art was gradually brought back to the museums and recognized as real art. Here we show two artists whose work was included in this show were Max Beckmann and Ernst Barlach, both collected by the Van Abbemuseum. The works exhibited here are quite similar to those on show in Entartete “Kunst”.

Ritual-Ethnology-Art

This sculpture comes from Sumatra, Indonesia, once used in a ritual ‘death dance’, before it was desacralized and included in an ethnographic museum as an artifact from a faraway land. Then it was declared to be a work of art (artization) and exhibited in an art museum. It is now presented as an artifact, dearticized, so that it can remind us of the different roles it played in different stories.

Two stories especially are interesting to recall. One is the relation between this ritual art and the modern avant-garde. Modern artists, like Picasso, were inspired by ritual masks, whose non-traditional forms they celebrated as ‘primitive’. Even if they understood ‘primitive’ as something positive, one can wonder if these ‘primitive’ artists were grateful for the etiquette, which reminds of the colonial tradition to consider other cultures as backward.

The other story links this mask with the Van Abbemuseum. This mask was made in Sumatra Utara a region from which Henri van Abbe bought the tobacco to make his cigars. This tobacco was grown under colonial rule in Indonesia. It testifies to the complex relation between the West, its modern art and its colonies. The innovation of modern art was inspired by ‘primitive’ cultures, who were kept ‘primitive’ within the colonial world order.

*******

If art is one of the inventions of modernity, then the display echoing the Alexander Dorner’s “atmosphere room” representing the Middle Ages seems to be an appropriate environment for de-artization as a “non-modern” view on modernity.

Room 3 Cubism and Abstract Art

When The Museum of Modern Art opened in1929 it was in a five room rented space and without a collection. In its first press release just before the opening it was stated that this museum would be a temporary place for keeping and exhibiting modern art as illustrated on Alfred Barr’s diagram “Torpedo in Time”. According to this idea, all works that become older than fifty years would be transferred to the Metropolitan Museum. This was in essence a fixed interval that was moving on time line with both ends open.

However, at the 1936 exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art intended to historicize the avant-guard art of the first three decades of the 20th century, Alfred Barr came up with another kind of diagram. It was shaped as a genealogical tree with one end (beginning) closed around 1900′ while the other end was open toward the future.

Instead of the “National Schools”, a concept established to structure the art history, this diagram introduced the opposite concept: “International Movements”. This approach completely reshaped the modern art at the time when modern art disappeared from the museums in most of Europe. After the WW2 this new narrative was eventually adopted by the European museums as well and remains as the modern canon until today.

*******

The exhibition “Cubism an Abstract Art” is placed in a White Cube space characteristic for the Museum of Modern Art in New York that was adopted by many museums of modern and contemporary art.

A footnote: at the beginning of this installation illustrating the “MoMA Canon”, as an example of a cubist painting, appears the “Woman in Green”(1909) by Picasso from the museum collection. It so happened that the same painting was necessary for one of the de-artsation stories in the previous room illustrating a public outrage apropos the acquisition of this painting for the museum collection. Since the same painting could not appear in both stories simultaneously, it was decided that in the de-artization room hangs original, while in MoMA room is used its copy.

After a while a museum person responsible for the museum collection noticed an interesting detail regarding the wall label next to the copy: “Throughout the years I have cleaned and replaced this card quite often because people touch it all the time. I find it very interesting that the things they point out are ‘copy’ and ‘loan from Museum of American Art, Berlin’. Other works from MOAA do not have this (as much), only the copy of our Picasso. The anthropology of the museum visitor should be a study on its own”. Perhaps, next to the usual museum’s warning “Don’t touch art”, it ought to be added another one: “Don’t touch label”.

In addition for being an “anthropology” case, it is a good example for the Benjamin’s observation that copy enables a work to appear at the same time in two different stories and in two different roles.

Another similar example at this exhibition is painting by Piet Mondrian “Composition 2”.

In the de-artization room both original and copy are hanged next to each other, and in MoMA installation where the second copy is at the end of “geometric abstraction” line. In the de-artization case original is an abstract painting, while its copy, according to Benjamin, is in fact representational/realistic painting. However another copy of the same painting hanging in MoMA’s room is representing the Geometric Abstract Art from Barr’s diagram.

Two copies of the same abstract painting in two different stories and with completely different meanings. In other words, a copy of an abstract painting is not only a realistic painting, but it can also play a role of an abstract painting as well.

Room 4 Van Abbemuseum 1936

Opening of the Van Abbemuseum was an important event in the history of Eindhoven. Initially it had a modest collection of contemporary art, which might have been a reflection of the atmosphere in the art world in Europe at that time, unfriendly toward modern and Avant-guard art.

Around the year 1936, when the museum opened, a few important events took place in the art world. In Germany all the modern art was being removed from the museums including the Landesmuseum where the Abstract Cabinet was dismantled. All these confiscated works appeared the next year at the exhibition mocking modern art titled the “Entartete kunst”; at the same time Picasso presented his monumental painting “Guernica” in the Spanish Republic pavilion at the International Exposition in Paris.

That same year 1936, across the ocean, at the exhibition “Cubism and Abstract Art” the Museum of Modern Art presented a new history of the European modernism that included the Russian/Soviet avant-guard, while in the Philadelphia Museum of Art opened an exhibition “Soviet Art” promoting Socialist Realism. Only a year earlier, back in the Soviet Union, the First Exhibition of Leningrad Artists took place, which included four portraits by Malevich while he was in his deathbed and died during the exhibition. This was the last time works by Malevich were exhibited in the Soviet Union for many decades and could be seen only in New York at MoMA and afer the WW2 in the Venice Guggenheim Collection and Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam.

In the years after the war, Van Abbemuseum opened toward modernism as well and begin including some important modern works that culminated with the acquisition of the Lissitzky collection for which the museum became widely known.

********

This is a partial reconstruction of the first exhibition of the Van Abbemuseum based on the photographs of the installation views. It reminds us how from its humble beginning Van Abbemuseum managed to become one of the most advanced museums today.

Room 5 Eight Exhibitions

There were many important exhibitions of modern art in the 20th century. Here is a selection of only eight of them, all from the first half of the century, that are worth remembering, since they significantly influenced the story of modern art as we know it today.

It spans from the 1905 Stein’s collection when for the first time paintings by Cezanne, Matisse and Picasso were hung together, to 1948 (re)construction of Neoplastic Room in the Museum Stzuki in Lodz and exhibition of the Peggy Guggenheim collection at the Venice Biennale when for the first time modern European art (including Malevich and Lissitzky) was shown in Europe together with Abstract Expressionists.

It includes the 1926 International Exhibition of Modern Art in the Brooklyn Museum organized by the Societe Anonyme, the exhibition of Kazimir Malevich at the 1927 Grosse Berliner Kunstausstellung, the Abstract Cabinet by el Lissitzky installed in1928 at the Landesmuseum in Hanover, and two cases of exhibitions that were anti-modern art: the 1931 Exhibition of Bourgeois Art in the Tretyakov Gallery (Moscow) and traveling exhibition “Entartete kunst” shown in Germany 1937.

And here is another version of the introductory text for this room:

Eight Exhibitions – 2. version

If an art exhibition is a story, then the history of art is a story of stories. This room presents eight exhibitions that played an important role in the history of modern art in the West. It is a story of consonant and dissonant voices. On the outer wall you will find displays of six exhibitions, important to the narrativeof modern art championed by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. These exhibitions were made by visionary collectors and brave curators who collected and showed artworks that are now revered as classical avant-garde.

In the middle of the room two dissonant exhibitions are presented: Art of the Industrial Bougeoisie (1931) in the Tretyakov State Gallery, Moscow and the travelling exhibition Entartete kunst (Degenerate Art) shown in Munich 1937. These two exhibitions considered modern art a problematic or even abject derailing of art. Both the Soviet Socialists and the National Socialists understood modern art as an expression of the waning bourgeois world that their totalitarian systems surpassed. It is also in opposition to these Soviet and Fascist views that the West embraced its radical art as iconic of freedom and progress.

The setting for this story of stories is inspired by the Lenin Museum in Moscow. As this exhibition is situated within the West, but attempting to look at our history from a distance, this historical museum in the East seemed a fitting setting to emulate.

Gertrude Stein’s Collection – Paris 1905

Here is the story of Gertrude and Leo Stein, who assembled the earliest and one of the most influential collection of modern in their house in Paris in the beginning of the 20th century. The well-visited salons Getrude Stein organized, have had a lasting influence on the story of modern art.

Their modern art collection started, when in 1903 they acquired a few Paul Cézanne paintings, including the Portrait of Madame Cézanne . In 1905 they met Matisse, after the public scandal that followed the first appearance of the Fauvists, an artist group of which he was prominent member. From him they bought La femme au chapeau (Woman With the Hat), 1905. Within a few weeks, they also met young Pablo Picasso and acquired his painting Girl With the Basket of Flowers (1905).

This was perhaps the first time that paintings by Cezanne, Matisse, and Picasso could be seen exhibited together in one room. Three decades later, in the exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art (1936), Alfred H. Barr Jr., the director of the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA), who had also visited Stein’s salons, established his narrative of modern art. He began with Cezanne and would branch out in two lines, one would go toward Matisse and another, toward Picasso – just as it was anticipated in Steins Salon.

International Exhibition of Modern Art – Brooklyn Museum 1926

In 1926 the Société Anonyme, an organization which supported experimental art founded by collector Katherine Dreier and the artists Man Ray and Marcel Duchmap, organized a remarkable exhibition of modern art in the Brooklyn Museum. This seems to be the first exhibition that exhibited together works of modern art from Europe, Russian/Soviet Avant-Guard and modern American art. Although in the catalog the artists are grouped by nationality, it judging by the installation views it seems that the exhibition itself was structured by artists as individuals.

Société Anonyme was also one of the earliest collection outside of USSR that included a paintings by Kazimir Malevich, The Knife Grinder (1912-13). It was acquired by Katherine Dreier at the Erste Russische Kunstausstellung (First Russian Art Exhibition)in Berlin 1922. This was the first work by Malevich that entered an American collection, perhaps even the first in any foreign collection.

Kazimir Malevich – Grosse Berliner Kunstausstellung 1927

The Grosse Berliner Kunstausstellung (Great Berlin Art Exhibition)(1927) was the first major Kazimir Malevich exhibition outside of USSR. The reason why we celebrate Malevich today is the result of the adventurous reception of this exhibition.

After the exhibition, all the works were brought to Provinzialmuseum (now Landesmuseum) in Hannover and placed in the custody of Alexander Dorner. In 1935 the director of the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA) Alfred H. Barr jr. came to Hannover and took six paintings from Dorner for the exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art (1936). Malevich has been exhibited in MoMA ever since.

Before Dorner left Germany in 1937, Hugo Herring, a friend of Malevich, took all his works from the museum to keep them safe. Twelve years after the Second World War, the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, managed to acquire all these works and so held the largest collection of Malevich outside of the Soviet Union. And so it happened, that for many years after 1927, until 1989, if you wanted to see works by Malevich the best places to go were Amsterdam and New York.

The Abstract Cabinet – Provinzialmuseum, Hannover, 1927

The Abstract Cabinet (1927) emerged out of a close collaboration between director Alexander Dorner of the Provinzialmuseum (now Landesmuseum), Hanover, and the prominent Soviet Avant-Garde artist El Lissitzky. After the opening, the cabinet became one of the most prominent exhibits of the museum. It inspired museum professionals worldwide. Alfred H. Barr jr., director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA), stated: “The Gallery of abstract art in Hanover was probably the most famous single room of twentieth century art in the world.”

With the rise of National Socialism in Germany, it became impossible for Alexander Dorner to keep the Abstract Cabinet open for the public. It was finally dismantled by the government in 1936. After the Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art)(1937) exhibition, which included pieces once displayed in the Cabinet, the artworks were confiscated and eventually destroyed, while Dorner fled to America. The spread of Fascism provoked a temporary end of modern art in Europe.

The Peggy Guggenheim Collection – Venice Biennale 1948

During the first post-war Venice Biennial in 1948, Peggy Guggenheim decided to bring her collection of modern art to Europe. The Biennial organization gave her the Greek pavilion to show her collection, as Greece couldn’t participate due to the civil war. It was one of the first post-war European exhibitions of what we can now call, the classical canon of modern art.

It was the first time after the war that Europeans could see works of most important modern artists as Picasso, Miro, Ernst, Mondriaan, including two members of the Russian Avant-Guard Malevich and Lissitzky. These modern artists were combined with American abstract expressionist painters as Jackoson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, Gorky. In both the catalog and the exhibitions the artists were treated as individuals regardless of their country of origin.

In the next few years the Guggenheim collection was exhibited in Milan and Florence (1949), as well as in Amsterdam, Zurich and Brussels (1951). Willem Sandberg, then director of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, had helped Guggenheim to bring her collection to Europe. As token of gratitude, she decided to give to the Stedelijk five paintings by Jackson Pollock, the first to enter a European museum collection.

This 1948 Guggenheim exhibition was designed by Carlo Scarpa.

Neoplastic Room – Muzeum Sztuki, Lodz 1946

The story of Neoplastic Room started in 1946, when Muzeum Sztuki, Lodz moved to its new location: the 19th century palace of the industrialist Maurycy Poznański. Director Marian Minich then invited Władysław Strzemiński to help design the new exhibition rooms. The artist was entrusted with the task of designing the space that would contain some of the works from the collection of European avant-garde. This collection was gathered during 1920′ on the initiative of the members of the “a.r” Group and became the foundation of one of the earliest museums of modern art that opened in 1931.

The Neoplastic Room, as it was called, was opened in 1948 and it immediately became its main attraction. Unfortunately, it was not for long as the room was painted over and the works deinstalled in 1950. Both the design of the room and the works were deemed inappropriate from the perspective of the new official Social Realism-doctrine, which favored realistic, celebratory representations of the socialist state, over abstract art. The Room was reconstructed in 1960 by Strzemiński’s student Bolesław Utkin. Since then, and today it is one of the focal points of the permanent exhibition of the Museum in Lodz.

Bourgeois Art – Tretyakov Gallery 1931

A few years after the October Revolution some art theoreticians and museologists started to think how art should be exhibited in the new, socialistic society. They concluded that if ,at that point, socialism is the most advanced form of society, then its art should be superior from art of previous epochs. Art theoretician Fedorov-Davidov translated these views into exhibitions that were titled Bourgeois Art(1931-33) displaying paintings by Kandinsky, Malevich and Rodchenko, produced before the Revolution, with large labels like “Formalism” next to the works, even “Self-denial” next to the Malevich’s famous Black Square (1915). On top of the wall was a long banner ”Dead-end of Bourgeois Art”.

In this manner modern, abstract art was shown as product of capitalism, telling visitors not to admire it. Instead realistic art celebrating Soviet-society, known as Socialistic Realism, was exhibited as true and superior art. In the end all modern/abstract works, particularly paintings by Malevich, Tatlin, Rodchenko, Lissitzky,etc. were labeled as formalistic and placed in the depot. They stayed there for many decades and until the end of the Soviet Union remained hidden from the public. During all these years, the term “formalism” remained the key-word for dismissing abstract art.

Entartete Kunst – Munich 1937

Under National-Socialist rule in Germany in the 1930s and 1940s, a decision was made to remove modern art from all museums in the country. In advance of its disposal in one way or another, modern art was presented in an exhibition that toured Germany in 1937, mocking and disparaging the work as ‘Bolshevik’ (Communist), Jewish, and insane. After the defeat of National Socialism, modern art was gradually brought back into the museums and recognized as art.

The cultural campaign of the National Socialist was directed against expressive and abstract art, favouring glorifying realism and picturesque representation of the German country. It not only rejected visual art, but also branded a-tonal music and jazz ‘entartet’. The Entartete Kunst exhibition were very well visited, the Munich-edition alone was counted over two million visits. Considerably more than the 420 thousand visits to the Grosse Deutsche Kunstausstellung (Great German Art Exhibition), which showed art celebrated by the Nazis. During the German occupation the exhibition Wansmaak en Gezonde Kunst (Bad Taste and Healty Art) (1943) was organised, in line with Entartete Kunst and the Grosse Deutsche Kunstausstellung. This exhibition was shown among others at the Van Abbemuseum, but no photos of the exhibition remain.

*******

Since the approach in this story of exhibitions is historical, its design is based on the display elements and techniques used in the Museum of Lenin in Moscow.

Room 6 Raum der Gegenwart

The Western modern world was based on specialism. Art, technology, culture, all were worlds apart. However, periodically everything was brought together and exhibited in immense festivals known as World Exhibitions. This room recalls three of them, which show the complex simultaneity of three modern phenomena: art, technology and colonialism.

The exhibitions presented are the World Exhibition of 1936 in Paris, remembered for the presentation of Picasso’s famous painting Guernica, made in response to the Fascist bombing of the village Guernica. The Paris exhibition also included a famous confrontation between the Soviet Union and National Socialist Germany. The second exhibition is the 1939 exhibition in New York. Here robots and high art shook hands, a classical modern spectacle of culture. The last exhibition presented here is the Brussels World Exhibition of 1958 with its iconic Atomium, but also with a unique pavilion made by the Philips corporation, designed by architect Le Corbusier, which showed the remarkable film Poem Electrique. And, as a dark shadow, all exhibitions included eroticizing displays from the colonies, which remind how the West bought its progress at the expense of others.

The design of this room is based on the unrealized design of Lazlo Moholy-Nagy, who was commissioned by museum director Alexander Dorner to make a Raum der Gegenwart (Room of the Now) and includes a reconstruction of Moholy-Nagy’s Licht-Raum Modulator. This was one of the first museum design intended to bring together all aspects of life, letting go of the rigid boundaries between art and life, as such a fitting setting for these World Exhibitions.

When Alexander Dorner invited El Lissitzky to design the room for abstract art named the Abstract Cabinet, this was intended to be just one of the series of “atmosphere rooms” of the Landesmuseum in Hanover. Connected chronologically these rooms would take visitors on a journey through history proudly displaying the brightest moments in the history of art. From the Abstract Cabinet, that would show the most advanced achievements of the immediate past, visitors would enter the last room which was devoted to the present, the Room of Our Time, designed by Moholy-Nagy. It seems that this would have been the end of a long journey that begins with ancient times and culminates in the present. But, what would be shown in this room as “our time”? The time of the 1930es when it was conceived or, perhaps the never ending present?

In this contemporary (re)construction of the Raum der Gegenwart the “present” is imagined as an interval that begins in the mid 19th century and ends today. The main feature of this interpretation of present is the notion of “globalization”, an attempt to see the entire world as one and all the people as its citizens. The development of this idea is here traced through the history of World Fairs, international exhibitions of industry and art, that started 1851 in the London Crystal Palace and since then continue to be organized in all parts of the world.

*******

The design of this room is based on the original plans by Laslo Moholy-Nagy for the Landesmuseum in Hanover that was not realized.

Room 7 Western Art

Western Art We, from the island Utopia, are honored and proud to present to you this unique collection of Western Art, once held by the famed Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven. Since we first learned of the West, through an adventurous traveler Raphael Hythlodaeus, who visited our beautiful island more than 500 years ago, we have been fascinated by the West. A humble scribe, a certain Thomas Moore, later wrote an interesting book, Utopia, documenting the specificities of our culture, which in many ways diametrically oppose the West. Still, the art of the West also speaks to us, and it gives us great joy to show all these works together, even if perhaps we cannot know if our organization reflects how these works were shown in Eindhoven. Yet, we understood from studying the West that even within the West artefacts were shown in manners that sometimes conflicted with their ‘original’ meaning, we therefore feel confident, that this display in this sense is even in line with the spirit of the West

Instead from the Utopia, originally the the collection was meant to be coming from China that explains the display design and this short explanation: “If we assume that the notion of art is not universal but a relatively recent invention of the western culture, it would be interesting to see how those artifacts named works of art that are products of this invention could be perceived from a different culture. Here is a selection of works of art from the collection of the Van Abbemuseum exhibited as if they belong to a museum in China named the “Western Art”. While “turning unknown into known” is one of the important aspects of modernity, there is a chance that through this kind of exhibit we get a sense how the reverse process ”turning known into unknown” might look like.”

******

The display design of this room is based on the exhibition techniques of the museums in China.

Room 8 Not-now

The pictures before us represent scenes of times gone by. They were all icons in stories of religion and of art. Some depicted events from the past, while others anticipated the future.

Today, they are nothing more than artifacts displayed here neither as art nor as religion. While the pictures of the future became antiquities, the world emerging before us begins to resemble stories from the distant past. In a way it seems that the differences between the future and the past are disappearing, as if they are both becoming the one and the same meta-time that is not-now.

Walter Benjamin Recent Writings

Appendix 1

On Museum Rituals

In the far west of European territory, there is a land the natives call the Netherlander, widely known as the Low Countries. In one of its settlements, a town named Handwoven (may have the meaning “last hives on the land of Senseless”), there are various places for communal gathering, from smaller where people go to eat and drink called “restaurants” or ”bars”, to larger ones like a tall building with the big neon word “Philips” on top of it, or several temples of worship including one in the center of town called “Sint Catharinakerk”, or another big place, the “Stadium” where mostly man gather to watch games, or a place where locals acquire goods called the “Shopping Mall”, and several places with the name “Museum” where people go primarily to look at things and hear the stories told by the “museum guides”, but also to buy books, souvenirs, in the “museum shop”.

One such place is the “Van Abbemuseum”, an imposing conglomerate of buildings of various styles on the bank of the Dommel river, specialized in preserving and presenting objects called “works of art” that are admired in this society. Seems that even some privileged individuals are able to collect and proudly display such objects in their homes. It is not easy to explain what work of art is, since there are various kinds of objects in the museum that have a special, in many ways, sacred status. It appears they are admired by the visitor because of their beauty, but it might not always the case. The objects are presented in a special order that would illustrate a certain story that is told usually to a group of visitors by the museum priests called “guides”.

Many of these artifacts are hand painted images (“paintings”), and handmade objects, ( “sculptures”), but there are numerous kinds of art objects or “exhibits” in the museums that do not fit in these categories. This makes difficult for a visitor to identify and separate a work of art from a common object. One way to identify work of art is the “label”. Usually it is a piece of paper or a cardboard placed next to the object on which are written some key information about the artifact: name of the producer “Artist”, the “Title”, dimensions, the year of production and an information to whom work belongs and in some cases its provenance. Also, if a uniformed person, “museum guard”, that protects works from the visitors, warns not to touch it or get too close to an object, then this must be a work of art. In principle, one could recognize if the object is work of art by a certain sacredness that surrounds it and the special rules in relation to it, that the visitors should follow while in the museum.

Often visitors have to pay (buy the ticket at) the entrance in the museum where they will get a special sticker and place it on their chest so the guards will recognize a legitimate visitors. Those who do not display the sticker will be approached by the guard, and if can not produce a proof that they paid the entrance fee, they will be escorted out of the museum. One can also notice people wearing a special tag in a plastic wrap, with a name printed on it. Those are people working in the museum, the “museum staff”. There are also “visitor” tags for the guest of the museum, or “artist” for a person installing her/his work in the museum. The museum visitors are expected to behave properly, not to speak loud, not to touch works of art, not to bring food or drink in the rooms (galleries) where works of art are put on display. However, at one end of the museum there is a special place where visitors could consume food or drinks, called the “Museum Cafe”.

Occasionally, there are special events in the museum, called the “Openings” that could be recognized as a rites of passage, since they mark the transition from a previous orderly state(old exhibition) to the next orderly state(new exhibition) after passing through a state of disorder(removing the old and installing the new exhibition) . One such event took place recently in the Van Abbemuseum at the time of the autumn equinox(transition from summer to autumn), for the introduction to the community of the new display of art throughout the entire museum, that lasted three days. The entire event was titled “Demodernizing the Collection” and consisted of three distinct parts, one for each day.

On the first day was the “Deviant Researching Symposium” that took place in a special enclosed large dark room(“auditorium”) with many seats covered with red fabric, all facing the platform(“stage”). On the stage was small table with few chairs and one tall stand from where a selected members of the group(“speakers”) would talk to the group.

A part of the stage was a big flat screen on which, in a certain order, will appear images or text apparently related to the each individual talk, since speakers would, during the talk, occasionally turn toward or point at the picture on the wall.

In one corner of the room was a metal stand with a video camera, on it and there was one person handling it. When at some point I cam behind this object, i noticed a small picture glowing from showing the stage. This device would record everything what was happening on the stage. There was also a person that was going around with a smaller camera holding in his hands ad taking pictures usually of someone who was talking. For each part of the talk, there was a person assigned to hold the “microphone”, a device that would amplify the voice throughout the entire auditorium. This same device was used by the people on the stage or someone in the audience. Many people in the group were writing notes on small notebooks while quite a few were looking into little bright screen of their phones they held in their hands and occasionally taking pictures with it.

First day gathering began in the morning, and lasted until early afternoon. There were several speakers, each introduced by the person who was the leader of the event, and after each talk people in thee audience were asking questions. At the end, a few speakers came to the stage and engaged in conversation and answered the questions from the audience. After the morning gathering ended everybody went to the museum cafe where food and drinks were waiting to be picked up. Specially arranged pieces of round bred(“sandwiches) filled with various vegetables, cheese and dry meet were available on the tables throughout the entire place, while a couple of people were walking around offering a hot soup. There, while enjoying the food many of the participants engaged in friendly and informal conversations. After a while people were invited to get back to the auditorium and the entire morning ritual was repeated in the afternoon. Later that evening a group of participants was taken to a nearby restaurant for a communal diner. That was the end of the day one of the museum opening ritual.

The major event of the second day titled “Decolonizing, Demodernizing and Decentralizing?” took place in the museum auditorium as well and was structured the same way as the previous day gathering. But before, there was a presentation and conversation related to the previous day theme. Then came guided tours by the main museum representatives through the two new major museum exhibitions: “The making of modern Art” on the ground floor and “Way Beyond Art” on the upper floors. After the tours everybody gathered again in the auditorium to hear the main talk that day that was about “decoloniality and end of contemporary” after which two participants commented the presentation. Then came the “lunch brake”, this time various food was served on one long table so that anyone was able to make her/his own meal. After the lunch everybody went back to the auditorium to hear the next speaker followed by two responses. Then the participants were divided in four groups “workshops” and gathered on for different locations in the museum. It became clear that for some reason the structure of that day events was more complex then the previous day. After the “mini brake” and the “Panel discussions” the main closing event of that day in the auditorium was the “Plenary Discussion” guided by a “moderator”. Later that evening, after the drink in the museum cafe, and continued informal meetings and conversations between the participants, a larger group of participants was taken to the restaurant for the communal dinner where informal meetings and conversations continued.

The third day during the morning and early afternoon hours, was a closed meeting of the museum association “L’ Internationale” which member is Van Abbemuseum while throughout the museum were organized various guided tours, concerts and workshops. Later in the afternoon the formal opening of the new exhibitions was announced by speeches of the head of the museum and a representative of the community of the town. After that a dinner was organized for a selected group, mostly members of the L’Internationale while throughout museum the was staged the “Young Art Night” with live pop and rock music music throughout the museum galleries.

*********************

This visitor(observer) is coming from a place/culture where there are paintings, which are kept only at homes and temples, but where there is no notion of art and human creativity, and where there are no exhibitions, galleries and temples called art museums. If concepts like art, museums, history, culture, ethnology, society etc., are product of the western culture(invented and articulated in the West), is it possible at all to observe/ interpret these concepts from some other “society” X while remaining outside of the West? This would include language, customs, social structure, dress code, food, ideology, set of beliefs, value system, etc. Since the entire society is like a single living organism, would it be possible to articulate this non-western position of some society X without using western concepts? Especially today, when all non-western cultures are, one way or another, already “contaminated” by the West and its view of the world, its concepts, values and terminology, including this writing and its language.

If two “cultures” are internally coherent, like for example chicken and frog, the question is how to translate the features of one culture into another? In this case the chicken’s beak could be translated into frog’s mouth, chicken feather into frog’s skin, chicken’s wings in frog’s front legs, etc. While it seems it would be possible to establish some correspondence between chicken and frog, this will be much more difficult between chicken and octopus. Also, it is important to determine the direction of translation. In other words, which culture is in the position of the “observer” and which in the position of being “observed”. Perhaps it might be necessary to establish/define a referential position/observer from which will be possible to observe both cultures in a “neutral” way, and the transition process as well.

Exhibition customs and rituals

installation/hanging

opening

Exhibition opening rituals

-opening speeches(museum representative, community representative).

-guests and audience/visitors

-cocktail in the museum restaurant

-dinner for the selected guests

-guiding tours through the new museum installation

-accompanying events(conference before the opening, concert in the evening after the opening)

sacredness

-secular sacredness of the work of art, artist and the art scene.

-fetishism of work of art and cult of the artist.

-art history as a holly book – museum as a temple

-transfer from the religious sacredness of paintings into secular sacredness.

-market value sacredness

lunch/cocktail

visitors

guided tour

conference

lecture/panel

Appendix 2

Cultural rituals

Rituals and ritualized behavior could be recognized in many aspects of contemporary life including the “art scene”. They are real events but have symbolic meaning the way, lets say, a painting or an exhibition are both real/physical and symbolic.

Sacredness of the art scene most likely originates from the religious sacredness of paintings and sculptures. At some point they were desacralized in religious sense but at the same time became sacralized in a secular sense by being declared to be “works of art”. This secular sacredness of a work of art was gradually spread to its producer who became an “artist” and the place where it was shown to the public-gallery or museum. To works of art are assigned properties of uniqueness and originality, and some of them are declared to be masterpieces. An artist became the author, “creator”, in a way a sacred person who in some cases plays a guru like role of an admired social leader with many followers (Joseph Beuys, Marina Abramovic). A belief in human creativity became the foundation of the entire art domain.

Sacredness(fetish) of an artifact in a religious context that derived from the ultimate creator(god) is transferred to its producer(maker) and it is how the cult of the artist (author) emerged and with it the fetish of the signature, authenticity, originality, etc.

The secular sacredness of an art object is manifested through its handling, usually by limited number of people (professionals) who had to wearing gloves. Similarly when a had of a household goes to the forest to cut an oak brunch for Christmas, he has to ware gloves in order not to to touch the sacred brunch with bare hands.

The sacredness of an art object put on display is manifested through various restrictions. There is a limit how close visitor/observer can get to the work, usually marked by a rope, line on the floor and alarm sound. Usually there are limitations for taking pictures at the exhibition.

The fetish of an art object is not only in its symbolic value but also in its financial/market value, although turning a religious painting into commodity represents in some way its desacralization. The market value of an artifact(including work of art) most often doesn’t relate to its intrinsic value or craftsmanship (“ rusty nail from the cross” or “ready made”). It primarily depends of the narrative in which the artifact plays a role. The more important is the story and the role of the artifact in it, the greater will be its symbolic and market value. Similarly the importance of an author, the degree of his/her sacredness, corresponds to its role in a dominant narrative(Canon), in this case the History of Art.

Humans are not creative, but belief in human creativity led to the production of numerous artifacts named works of art. However, the existence of these artifacts is a proof of human creativity as much as the religious artifacts and temples/churches are proof of the existence of god. In both cases these artifacts are products of certain beliefs but they are not proofs that those believes are founded in reality.

Although the concept of art is based on illusion of human creativity and as such is becoming obsolete, the art scene might still continue to exists not only because of inertia and a huge infrastructure built around it, but also because of certain social immunity it offers. Namely, a person claiming to be an artist could do things on this stage, as on a sacred place, that would not be possible in the real world. Something like a contemporary court jester.

It is necessary to keep in mind that observing western rituals (religious and secular) is still looking at these phenomena through the western eyes, through the scientific disciplines such as ethnography, sociology or anthropology.

There are three kinds of art related secular sacredness: sacredness of art work, of artist and of art scene(museums, galleries, events,…), and we could observe certain rituals related to all these three categories. They most likely derived primarily from the religious sacredness of the (religious)paintings and sculptures(that were at that time not “art” in present sense), and from the sacredness of the the temple and the dominate myth(or Bible), while there was no sacredness of the producer/maker (“artist”), except a certain respect as a good meister. The sacredness of a painting as art and its maker as an artist most likely came with Romanticism together with the idea of human creativity.

From the Unpublished Manuscripts