Museum of Modern Art

Once upon a time, far away in the East, there was a Great Nation proud of its rich culture and tradition which had flourished on this vast land for thousands of years. Being blessed with such a long history, people of this land lived through many rich and happy years. They witnessed times of ascent and prosperity, but also times of stagnation and decline. After one such long period of uncertainty and poverty, signs of change and optimism could be seen everywhere. The new culture was beginning to emerge, while unusual forms of art were appearing in many places. In the beginning, this new art, named “Contemporary,” looked very strange since its origins were in the West and it didn’t have much in common with the great masters from the past. Nevertheless, Contemporary art was embraced by many young adventurous artists attracted to the ideas of individuality and originality. For a few decades this art could be seen in many new galleries that opened in all big cities of the land. However, after a while people began to ask: “How could we have Contemporary art without art history? What is Contemporary art without the memory of Modern art? Where are our museums of Modern art? Wasn’t it the Modern art that invented the ideas of uniqueness and originality?”

It is impossible to know what would have been the answers to these questions, if one day in the southern metropolis of the land known as the Walled City hadn’t unexpectedly appeared a Museum of Modern Art. This was the most unusual museum, such that had never been seen before anywhere in the world. Indeed it had a magnificent collection of the most important works of Modern art of all styles arranged according to the famous diagram, from Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism to Abstract art, Suprematism, Constructivism, … later DADA and Surrealism. As if all the masterpieces of Modern art had been by some magic taken from the West and brought to the East, and this Great Nation suddenly became the owner of the entire Modern tradition. But It was a huge surprise and disappointment for everybody when it was realized that in fact non of the exhibited works were originals! Instead, these were all copies made by the local artists from the Walled City. Some learned people immediately began to ask: “What kind of Modern art is this? These are all worthless copies. How we could have Modern art without the originals? And we all know that the originals are in the great museum, far away in the West, called The Modern. That is the real museum of Modern art, not this pathetic imitation!”

What these wise men didn’t understand was that they were looking into the past, and it was only in the past that the originals were admired and valued, while copes were despised and considered to be worthless. They could not see into the future, since in the future they would see that it is the copes that are valued and respected , while the

originals are perceived to be simple and trivial. A copy of an original abstract painting will look just as abstract. But as a copy, this painting will also be realistic and representational. And, as time goes by, who knows how many new meanings that copy will acquire, how many new roles it is going to play.

That is why our Museum of Modern Art made of copies is not a museum of the past, it is rather a museum of the future. Moreover, by being Modern and non-Modern at the same time, it will become the only true memory of Modern art, the only true Museum of Modern Art in the entire world. This is how it happened that this Great Nation unexpectedly got not only its Modern art, but at the same time its first Museum of Modern Art as well.

From The Tales of the Artisans

MoMA Made in China by Walter Benjamin

Recently I had the honor to give a lecture at the opening night of the exhibition “A Museum That is Not”. The lecture was titled “The Unmaking of Art” and the audience and I were placed in a gallery full of paintings, all the icons of the early 20th century European modern art, the masterpieces of western modernity. The sight would be very much familiar to any art lover, but we were not in any of the great museums of modern art in the West.

In fact, we were in the Far East, in China, in the newly established Times Museum in Guangzhou, the paintings around us were not originals but copies – all made in China. Even the famous Alfred Barr’s “Cubism and Abstract Art”, here as a painting, was in Chinese, with the chronology moved a hundred years back in time, and all the corresponding works were dated accordingly, meaning that modern art began in China one hundred years earlier than it did.

Moreover, for the first time, as far as I can remember, I was Chinese and giving my lecture in Chinese. For me this was an entirely unusual event, and since then I keep asking myself: What might be the meaning of all this? What is this thing called “MoMA Made in China” and me appearing as Chinese?

Perhaps it is not possible to give any definitive answer yet, it will take time to see what might be the consequences of such events both in China and in the West. In other words, it is too soon to tell. But it seems that those two events represent a complete disregard for the fundamental notions on which art and art history are founded – originality, authenticity, uniqueness of the artifacts (“art works”) and the identity of the characters (“artists”, “art historians”, etc.), and its basic structure: chronology.

It is important to underline that the notion of an author/artist as a unique character is defined only in relation to the original works of art. Without the original work there is no place for an author/artist as in the case of the Museum of American Art and similar institutions based on collections of copies.

As an associate of the Museum of American Art in the last several years, I was able to recognize all the works on display. These are the same images one could see for many years now in the smaller version of the “Museum of Modern Art”, exhibited as an American “invention” at the Museum of American Art in Berlin. These images differ only in size. The paintings in Berlin are ten times smaller than the originals, and all visible from a single vantage point above. In the Times Museum the paintings are the same size as the originals, dictating that we walk through the exhibition like in any museum, and experience them from within. One might interpret these two cases as if our size as observers becomes relative, while the observed, the exhibit, remains the same.

These paintings, being copies, do not change their meaning by changing the size. That is one of the most important properties of a copy: regardless of its size, small or large, it will still represent the same original that is being copied. A copy is a symbol that stands for the corresponding original and, being a symbol, its size becomes irrelevant. Another important property of a copy and exhibits based on copies is the possibility to be replicated and appear in two or more locations simultaneously. Today, one can see the same copy of Cezanne’s “Bather” playing the same role simultaneously in three different versions of the story named “Museum of Modern Art”: one here in Guangzhou,

another in Berlin, and a third in Eindhoven. It’s worth noting that, at the same time, these three versions of the “Museum of Modern Art” themselves play three different roles within three different exhibitions (Guangzhou -“A Museum That is Not”, Berlin -“MoMA and Americans”, and Eindhoven -“Sites of Modernity”). A story within three different stories.

However, the copy is not the primary theme of the “Museum of Modern Art” exhibit, it is just a vehicle to tell the story about the origin of the modern canon called the History of Modern Art. This canon was formulated by the Museum of Modern Art in New York at the 1936 exhibition “Cubism and Abstract Art”, according to Alfred Barr’s diagram on the cover of the exhibition catalog. This was the exhibition that introduced “International Movements” instead of “National Schools” as a key notion in the Art History. Together with the uniqueness of the author, the art work and chronology it became the key ingredient of the story which defined the art world since then until today.

The first three walls of the “Museum of Modern Art” exhibit are arranged according to the main lines of this diagram, while the back wall reflects the exhibition “Dada, Surrealism and Fantastic Art” at MoMA, curated by Alfred Barr in 1936. Thus, the storyline of this exhibit ends in the year when the story itself was conceived. Being founded on the ideas of internationalism and individualism, this story gradually became the modern canon, first influencing and later incorporating all the subsequent developments/movements until the present. This is the story that brought the art world to here, the story out of which the entire art scene today emerged. And this is the story that has completely exhausted its potential and cannot take us any further. The story based on the uniqueness of its characters, artists and art works, and chronology will probably continue to be followed, but it will also continue to be more of the same. That story has no potential to open new frontiers, new visions, it cannot take us to unknown places.

In order to get there it would be necessary to start a process of detachment from the very notion of art and trying to look at an artwork as a human made specimen, as an artifact of a certain state of mind or certain cultural/political milieu, in this case the West. This approach should not be one of a passionate believer and admirer of art, but a diagnostic one, an almost cold approach of an ethnographer.

In order to fully establish this “dispassionate” position, some of the existing art museums would have to gradually transform into anthropological museums about art. Such would be a new kind of museum, one that would enable the de-artization of existing works of art into non-art artifacts, the way desacralization of religious paintings and objects changed their meaning by being removed from churches and placed into the art museums. This new kind of museum would be in fact a meta-museum based on a meta-narrative.

If the meta-narrative is possible, it should not forget the History of Art, it just has to re-contextualize it. However, a meta-narrative could not be built on the same fundamentals: uniqueness and originality of the author and artwork and on chronology. Those notions could not be constitutive for any meta-narrative in relation to the History of Art. When we analyze the properties of the “Museum of Modern Art” exhibit at the Times Museum we could come to a conclusion that it is not based on originality and authorship. It also makes relative the idea of chronology by moving the entire time line of Barr’s diagram a hundred years back in time, and dating all the works accordingly. Without respecting

the key notions of the modern canon: authorship, originality and chronology, this exhibit has positioned itself outside of Art History and the basic principles of the art context in general. The existing permanent installation in Berlin is already outside of the Western canon, but it is still in the West, while this “Museum of Modern Art” materialized in Guangzhou is not only conceptually but also culturally and even physically/geographically outside of the West. Furthermore, by translating the words on the paintings from European into Chinese transcript, from the western point of view this version of the “Museum of Modern art” could be interpreted as an “Orientalisation of the West”.

Finally, how to understand the meaning of the title “MoMA Made in China”? Since today it is common belief that almost anything could be copied in China, including art, to someone this title could sound like a superficial stereotype. However, is it really possible to copy such a thing as modern art whose very essence is belief in originality? Or is it possible to copy the Museum of Modern Art? Of course it is not.

Imitation or copy as notions is in antithesis with modern art. Having MoMA made in China precisely questions the Western belief in uniqueness and originality on which all modernity stands. The Museum of Modern Art based on a collection made of copies produced in China is not the Museum of Modern Art. It is a museum about the Museum of Modern Art. It is what makes “MoMA Made in China” the real museum of modern art, a place where modern art is really remembered and actualized, where this memory is more about the present and the future, then it is about the past.

It is also not so important that the idea for this collection is initiated by the Museum of American Art in Berlin, nor that it is produced in China (“MoMA Made in China”). It was practical decision, it could have been produced anywhere in the world and it wouldn’t have made much difference. The most important is the fact that this collection,

called “Museum of Modern Art”, with these specific properties (translations in Chinese language and chronology moved 100 years back) was for the first time exhibited in China. I wouldn’t be surprised if one day we have a chance to see “MoMA Made in France” in Paris, or even “MoMA Made in USA” in New York.

Walter Benjamin, Guangzhou 1911

A Memory on Modern Art: Interview with Walter Benjamin

By Nikita, Yingqian Cai

It is said that a Museum of Modern Art will show up in a museum in southern China in the near future and this very museum is a recreation of one founding exhibition in the history of modernism and it comprises only works of reproduction. We are all very curious about this upcoming event and had a chance to talk with Walter Benjamin, who had been a main proponent of reproduction and an observer of the museum’s formation.

N: As you had been present in most of the events initiated by Museum of American Art in Berlin and you have personally commented on the idea of copies as well as some of MoAA’s collections and recreations, is it because these reproductions are somehow your post-mortal propagator or you are just part of it?

W. I could see these collections and recreations as my, to use your words, post-mortal propagation. I also became a part of these events, since both copies and reincarnations of the characters from the Art History are some kind of repetitions.

I have been associated with copy and copying for some time now. I wrote and gave lectures on this topic. Since the Museum of American Art in Berlin is entirely based on copies it was natural for me to become associated with this museum. Let me try to explain why I believe that copies today might become more important than the originals on the example of the Museum of Modern Art collection that is being produced here in China.

As you know the Museum of American Art has been invited to participate at the exhibition A Museum That is Not at the Times Museum in Guangzhou. After some thought, we have decided to propose a collection named the Museum of Modern Art that will be produced locally. This collection is based on the historical exhibition “Cubism and Abstract Art” held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York 1936. On the cover of the exhibition catalog was a diagram describing the development of modern art in the first three decades of the 20th century. This diagram became the foundation of the History of Modern Art the way we know it today. The most important aspects of modern art are the ideas of individuality and originality. By recreating the Museum of Modern Art, not with the originals but with copies, we will not have modern art but a memory on modern art. We will see what modern art was. And this could be important for the context of China, which as far as I know didn’t have an experience of modern art in its past.

N: In China, we are very familiar with copies, which are part of our everyday life. Making copies are merely a way to make profits but not so much a violation of the author’s autonomy. Although we use reproduction or recreation when talking about this Museum of Modern Art, but for most people, they are still just copies. What are the real differences?

W: The idea of originality was invented in the West and it is not older than a couple of centuries. It is primarily defined through painting as a unique and exceptional product called a work of art, made by a unique and exceptional person called an artist. In a way the idea of originality is an essence of modernity. However, throughout most of the history of the West a notion of originality and artist as a unique individual was not known. A painter was just one among the craftsmen, just another kind of manufacturer not much different from a goldsmith or a cabinetmaker.

In a way it is the copy that gives the relevance to the original. Without being copied the original would be forgotten. But, paradoxically, the copy is a different painting; it carries another meaning from the original. This is why copy could define a story that is different from the Art History.

I believe that the importance of the idea of the original art work and unique individual called the artist is over. This concept has produced a period in art we called Modernism but its potential is now exhausted. By remembering Modernism through copies, through this concept that is its antithesis, we are in fact placing ourselves outside of Modernism but at the same time we are not forgetting it. We are just establishing a position to re-contextualize it, to place ourselves outside of Modernism and the story called Art History.

N: This Museum of Modern Art is one collection newly built by Museum of American Art in Berlin for this temporary exhibition of A Museum That is Not. In one interview, you mentioned that “the theme of the Museum of American Art in Berlin is all about the ‘invasion’ of post-war Europe by American Art”, what does this new collection have to do with the history of invasion and its original context, the so-called west, which includes America and Europe in general?

W: In the Museum of American Art in Berlin there is a small version of the Museum of Modern Art built of little copies of modern European art masterpieces. Although the subject matter of this little museum is only European art, the MoMA museum itself, it is exhibited as an American “invention”. We are not looking here into individual works of art, but the series of works that are put into a story. In this case it is the story of European modern art told by an American, the first MoMA director Alfred Barr. This museum opens in New York 1929 but for many years it didn’t include American art into its story since American modern art was perceived to be inferior to European. It is only after the WWII and the emergence of the generation called Abstract Expressionists that MoMA started looking seriously into American modern art and decided to promote it in Europe. Between 1953 and 1959 MoMA, through its International Program, organized a series of traveling exhibitions shown in the major European cities. These traveling exhibitions of American modern art shown in Europe are the main story of the Museum of American Art in Berlin.

With this new collection we are going beyond the western context. This is a story of original European modern art that was brought to America and put in the Museum of Modern Art, and is now, after so many years, materializing in China not through the originals, but through copies. If modern art didn’t exist in China there could not be a memory about it. With this collection we will now have in China at least a memory on modern art. By materializing all the masterpieces of modern art, and exhibiting them together in one place, the way that have never been seen before in China, we are opening a possibility that modern (European) art put in the story by Alfred Barr (an American), in this new interpretation based on copies become part of Chinese tradition. Since we do not believe in the importance of the idea of the original, having Museum of Modern Art recreated through copies in China could be the best expression of the spirit of our time. World of originals is the past, world of copies is the future. In fact, making copies is the only original thing we could do today.

N. It is commonly believed that we are not part of that history (of invasion), what kind of reflection are we projecting here?

W: It might be true that there was no modern art in China and that you are not part of that history. This might look as a disadvantage, but I believe there are some situations when a liability could be turned into an asset. There was a time when having a strong tradition was perceived as an asset, but we are approaching the time when having a strong tradition could become a liability. If you are a Dutch artist, you are inevitably seen in the context of Rembrandt and Mondrian, whether you like it or not. And if you are French, then your tradition are Delacroix and Matisse. But what if you are French and you think Matisse is not important for you, and Mondrian is? In this case you will have a harder time to embrace Mondrian if you are French. It is much easier if you are coming from a culture without a strong modern art tradition. If I am today coming from the culture without modernistic tradition I am in the position to choose my tradition. If I like Mondrian, I’ll take it, if I like Picasso I’ll take it, if I like Malevich, I’ll take it. Various traditions are being reinvented in all cultures all the time. In each moment we are deciding/negotiating what is my/our tradition, as individuals and as a society. And often what we choose as tradition has very little to do with the real past. For several decades you could see in China portraits of Marx, Lenin, Stalin and Mao. What these first three characters had to do with the China? Or what story of Jesus has to do with Europe, but this story is for centuries one of the main European traditions. Similarly in art, Cezanne, Picasso, Matisse, Mondrian, Malevich are not part of the American past, but they became part of the American art tradition. Today artists of the Russian/Soviet avant-garde like Malevich and Lissitzky are much more remembered and respected in Holland than in their native Russia. The question is not if you could choose your tradition. You could and this was happening all the time in all cultures throughout the history. And by choosing you are in fact making the tradition. The question is what tradition are you going to choose or make and more importantly where is this tradition going to take you? Tradition is not something that you could preserve and put in the vitrine, it is not a folklore that is being re-enacted during the holidays. Tradition is a living thing, it is changing all the time according to our present needs.

N: Does this Museum of Modern Art have anything to do with any other museums of modern art in the world? Why this idea of recreate one in China?

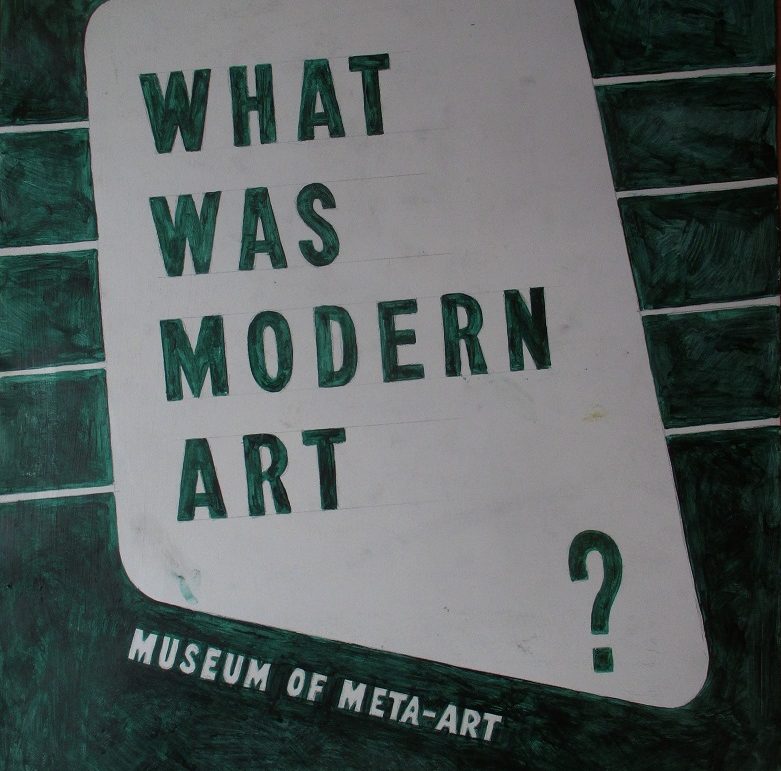

W: The subject matter of this Museum of Modern Art is the Museum of Modern Art in New York from its early period, when its story was based on European modern art. In that sense this Museum of Modern Art is direct reflection on MoMA from the mid 1930es. On the other hand this Museum of Modern Art is an antithesis of all existing art museums. In a way it is a Meta-Museum. All art museums are based on two unique categories, the original and the artist. In our Museum of Modern Art we do not have originals and thus we do not have artists. It is not an art museum; it is museum about modern art. In this museum art is presented ethnographically. Through this museum we are looking into art from the outside, as a specific Western invention. Similarly as an anthropologist would observe a foreign culture trying to understand it, but does not belong to that culture. On the other hand, by interpreting foreign culture we are in some way adopting it. By recreating this Museum of Modern Art we are showing how modern art could be interpreted and as a memory adopted in China. This might be one possibility how modern art could became a part of Chinese art tradition.

N: I understand this is not the first time of a complete reproduction of “Cubism and Abstract Art”, the famous 1936 exhibition of MoMA, originally this was part of “Sites of Modernity” which is now in the collection of Van Abbemuseum. But in the previous recreation, the copies are just 1/10 the size of the originals, so why the original size this time?

W. While in the case of the original painting there is only one size, a size of that single painting. But in the case of a copy the size could vary, in fact it is irrelevant. A copy can be the same size as the original, but it could be smaller or larger. This is possible since the copy is a symbol representing the original, while the original represents only itself. When we have a certain symbol then its size is not important. For example, a cross as a symbol of Christianity could be small or large but its meaning will be the same. In the case of the small Museum of Modern Art exhibited in the Van Abbemuseum, the size of copies is 1/10 of the originals, while here we have 1:1 copies. In both cases a little copy, let’s say of “Dance” by Matisse, will have the same meaning and play the same role as the large 1:1 copy. The only change is the relative size of the observer. While observing the Museum of Modern Art in Berlin we are looking at museum from above like giants, we could not enter and observe it from inside. Here in the case of 1:1 museum we will be able to enter it and experience this entire collection from inside. I think that would be very interesting experience since, as far as I know, the sight of these icons of the 20th century modern art as a full scale paintings exhibited together was never before experienced in this part of the world.

N: In this collection, there seems to be a lot of paintings. And you know we love paintings, our (Chinese) characters originated from drawings anyways. But you mentioned in various occasions that they weren’t art, I think we more or less already solved the question of “being art that are not paintings” in art history, but can they be paintings but not art? So how to look at those paintings as they aren’t art?

W. The tradition of painting in China is long and impressive, but a painting doesn’t have to be art in order to be admired or to be important. Many paintings today in the art museums were produced for some other purposes. For example, many paintings were made for churches and worshiped not as art but as sacred objects. People prayed in front of these paintings. After the Enlightment and separation of church and state it became possible to establish non-religious places like the art museums. At that time many religious paintings were taken from churches and brought to the museums. But in the museums they were not worshiped as sacred religious paintings, they now became art paintings. Somehow they became again sacred but in a different way. Instead of playing a part in the religious Christian story, these paintings became important in the secular story called the Art History.

If a religious (non-art) painting could become art it is legitimate to think that art-painting could become non-art by changing its context. That is one possibility for changing existing art paintings into non-art paintings. On the other hand, we could produce new painting whose subject matter is another painting. If the painting of a pipe is not pipe, than painting of an art-painting is not an art-painting. Sounds absurd but that kind of painting might not be a painting at all. (Painting of a painting is not a painting). This would be logical explanation why we consider copies, paintings of the paintings, not to be art.

Further more, those copies of modern art are not modern art because they are copies and not originals. But those copies could play a role in a story that is different from the Art History. We could call this different story a Meta-Art History. If a certain painting or object is art because it is in the Art History, then paintings and objects included in the Meta-Art History could not be art. This Meta-Art History would not be based on original works of art and unique characters called artists. On the other hand, the Meta-Art History is not forgetting Art History; it is just looking at it from the outside. In a way Art History is a story within Meta-Art history, a story within a story.

N: I also heard that MoMA’s first director Alfred Barr is one of the authors of this collection, how do you think of his work? What is your relationship with him?

W: We are very good colleagues and we have friendly and productive relationship. I am more a theoretical person and Alfred is more a practical museum person interested in exhibitions. As you know, we both died long time ago, but we died in the story called the Art History in which, as far as I remember, we never met. Now we are alive again playing in another story that is still unfolding. We don’t know yet what kind of a story this will be, but as I mentioned above, it is definitely a meta-story in relation to Art History. In this new story we not only know each other but we closely collaborate in the projects related to the Museum of American Art in Berlin.

N: Instead of histories, narratives are created. You also said that “In fact, this work contains its own context, its own narrative, so that you don’t need additional clues if you known modern Art History”. This Modern Art History seems to be the key to start a new reading, what about those who are uninformed of this history?

WB: You are absolutely right, in order to move outside of Art History you first have to know it, in a way you have to digest it. It is Art History that gives the meaning to the works it incorporates. Within Art History an abstract painting by Mondrian is a work of art. But for someone who is coming from a completely different culture, who doesn’t know anything about this Western story called Art History, the painting of Mondrian is just a piece of canvas painted with bright colors. This would be one way to be outside of Art History, by not knowing anything about it. Another possibility is to learn about Art History and become its believer. In that case you will recognize and admire this painting by Mondrian because you will know its meaning and importance in the Art History. There is a third possibility, to learn Art History but not being its believer (follower). In that case you will recognize this painting by Mondrian as an example of abstract art, but you would not admire it as a believer, you will just understand that some people who believe in art and Art History admire this painting. Basically, you have to know Art History in order to be able to overcome it.

N: For some people, these paintings are not even reproductions. They are productions without originals. These works may be the only visual connections with the never-existed originals, for those who have never been able to step into a so-call genuine museum. Sometimes you desire something stronger because you’ve never seen it, is this what you expect?

W: I would agree with you. Sometimes an open “lie” can bring us to the places where no truth can. This is why, for example, people have invented the theatre. In the theatre you could see a “murder” in a way you could not in reality. In the case of this Museum of Modern Art we will have a visual spectacle of masterpieces of modern art that would be very difficult to assemble anywhere in the world with originals. This is another example of the values of copy. We could create any story we could imagine with copies. For the experience that visitors will have it is irrelevant if these are copies or originals. Even in some very prestigious museums today originals are secretly substituted with copies in order to protect the original, so the visitors are looking at a reproduction thinking it is the original. In our case it is all transparent, visitors would know these are not originals, but what does it matter? As you said these paintings will give an experience of previously not seen images, brought together as a spectacle. And we think this approach is an example for the future. By the way, the distinction between the original and a copy exists only within Art History. There are many cultures that do not make this distinction. Even in pre-modern Europe this distinction didn’t exist.

N: If it is about the future, how do you envision the future of this Museum of Modern Art?

W: This Museum of Modern Art is not only about China, it is also about the West. Conceptually, being based on copies and not on originals, it is already outside of the existing Western story even when it is exhibited in the West (Germany, Holland). This outside position in relation to the West will be more emphasized now when the Museum of Modern Art becomes materialized physically outside of the West. In a way it might have one kind of effect in China and another in the West. I think for the West it would be very important now to be able to experience an echo of its own culture as something foreign, something strange. In other words, West has to be able to see itself from the outside.

For this Museum of Modern Art it is not only important that it is produced in China but, I think, this is where it naturally should belong. It might help in establishing an example how it would be possible to move beyond the story called the Art History without forgetting it. I also think that it would be important for the West to see and experience this Museum of Modern Art made in China. It might help them to see their own culture in a different way and to understand how they could move beyond the Art History. Perhaps this new story, this Meta-Art History will become the common story in which both China and the West would feel at home. This story is just beginning to be written.

Exhibition customs and rituals

Installation

Opening

Cocktail

Guided tour

Visitors

Opening dinner

Walter Benjamin: The Unmaking of Art – lecture

“Good evening.

The visitors of the this year’s Venice Biennale had a chance to see, among all the variety that contemporary art offers, three paintings by one of the Old Masters, Tintoretto, as part of the exhibition “Illuminazioni”. Among the paintings exhibited at Palazzo delle Esposizioni was this 1594 “Last Supper”. The painting was simply taken from the nearby San Giorgio Maggiore church and brought across the canal to Giardini, moving from a religious into a secular realm”…

….”A few years ago The New York Times Travel section published a picture of a priest in the St. Francois-Xavier church in Paris praying beneath another “Last Supper” also by Tintoretto. Recently this painting, too, was removed from the church and temporarily hung in the Napoleon Hall of the Louvre during the 2009 exhibition “Titian, Tintoretto, Veronese…”. As these two events illustrate, it is not unusual today to see a certain religious artifact, like a religious painting in this case, being temporarily desacralized and, after some time, returned back into a church and regaining its sacred properties. We don’t even pay much attention to what degree this kind of dislocation changes the meaning of the artifact”. ..

…”As we all know, the original destination for this religious painting was a church, and this is why this painting was made. Its importance lies in the characters of the Christian story called The New Testament, Jesus and the Apostles, and the event itself called the Last Supper. The identity of the painter, in this case Tintoretto, is incidental and irrelevant for the story. He was just a vehicle in God’s service, an executor of God’s will. When the same painting is exhibited in the museum, its role is completely changed. Now the main characters in the “museum story” called Art History are Tintoretto the artist, and the painting the “Last Supper”, while Jesus and the Apostles are of secondary importance, somewhere in the background, almost irrelevant. Simply, they are not constitutive characters of the Art History”…

…”Thus the painting itself now carries two different meanings, it plays two very different roles in two completely different stories. Its internal story is a religious one, The New Testament, while the external story, a “meta-narrative”, is secular, the Art History. Its original meaning was religious and the later acquired – secular. We may ask ourselves, how this became possible. How did it happen that a certain object can easily move from one kind of a place into another, from one story into another and completely change its meaning?”…

…”To find an answer to this question we have to go to back to Rome some five hundred years ago. When cardinal Giuliano della Rovere became the Pope Julius II, he brought this statue named Apollo with him and placed it in the Vatican garden named Belvedere. One day in 1506 ano domini, news about an excavation of an unusual statue reached the Pope, and he immediately dispatched Sangalo and Michelangelo to the site. Sangalo instantly recognized the priest Laocoon and his sons, mentioned in Pliny’s writings, the unfortunate characters of the mythical Troy. Not too long after, several more statues were placed in the garden in specially built niches on the surrounding walls, including the reclining Nile and Tiber, Apollo, Laocoon, Venus, Cleopatra, Torso.. and suddenly in the very heart of the Christendom a vision of a completely different world was beginning to emerge, a vision that would have profound impact on the entire western world for generations to come”….

…”The sight of the collection of broken statues from the distant past, placed in the idyllic Vatican garden, later named “Belvedere Romanum”, marks the birth of “Antiquity”. Also, as a novelty, being at the time a new vision of the world that was not Christian, it marks the birth of “Modernity” as well. And for a short period of time Antiquity and Modernity lived happily together in this magical garden with a beautiful view, offering a way out of the Christian universe. Those statues, previously almost invisible as scattered parts of an urban landscape, now displayed together, became “aesthetic objects” admired primarily for their beauty. It was almost irrelevant why they had been made at first place, what roles they once had played, what their internal narratives were. In today’s terms, we could consider these statues to be the first ready-mades and, in fact, the first objects of art, while the Belvedere Romanum could be understood as the first museum of art, and in that brief period even the first museum of modern art”…

…”Their immediate impact could be recognized on the contemporary masters like Raphael, Titian, and Michelangelo. Gradually these contemporary reflections on Antiquity became the Modernity, while Antiquity itself became identified with the ancient past. Those statues now became new, non-Christian, characters of a contemporary story about the distant past called ancient Rome. By being able to position oneself outside of the Christian narrative, it now became possible to recognize a crude three-pieces construction that became the foundation of the secular narrative called History: Rome – Christianity – Modernity (what we call the Renaissance today).

…”After Winckelmann’s observation of the excavations of Pompeii and Herculaneum and his interpretation of Greek art, the mythical ancient Greece became a reality and was added to the construction before Rome, while on the other end Modernity was already in the Baroque by that time. With Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt this ancient African civilization was included into European ancestry, preceding Greece on the chronological time-line, while on the opposite end it was already time for Neo-Classicism”…

…”Finally in the XX century two more chapters were added, the beginning moved one step back in time, from Egypt to Prehistory, while its contemporary on the other end became modernism, and the entire history and art history as we know it became completed. It would begin with Prehistory, followed chronologically by Egypt, Greece, Rome, Christianity, Renaissance, Baroque, Neo-Classicism and ending in Modernism. The story was organized along the chronological time line and as the methods of authentication and dating of the artifacts improved, the story became more accurate and copies were being identified and separated from the originals.”..

…”The introduction of individual characters into the story could be traced to Vasari and his 1550 book “Lives of Painters, Sculptors and Architects”, beginning with the earliest masters Cimabue and Giotto and culminating with Leonardo, Raphael and Michelangelo. By the beginning of the XIX century the notion of an exceptional individual called an artist was being well established and Alexander Lenoire in his 1824 book “Comments on the Genius, The Main Work of the Artist” could describe Michelangelo as ” Genius, original and individual”. A painter or sculptor was not just a craftsman any more, but a unique and exceptionally gifted individual, an almost God-like creator called an artist. And the corresponding artifact, named a work of art, became a masterpiece, also a unique and original category”…

…”But, what constitutes as a work of art? Is it an artifact that has defining intrinsic and unique properties that we could identify as art, or a special product made by an exceptional person called an artist, or an object that becomes art only when it is placed within a certain sphere we call the art context? And does it, and to what degree, have to do with craftsmanship?”…

…”At the time of Louis XIV, painting and sculpture were part of the guild system as they had been since medieval times. In addition to the subject matter, paintings and sculptures were mostly valued because of the craftsmanship invested in them, same as the other hand made products. It was important for a guild to keep high quality standards, and thus they had a decisive role in giving permits for the import of paintings and sculptures from abroad, even for the king. Initiated by the painter Le Brun, after his return from Rome, the Council of the ten year old king issued the “Arret du Conseil d’Etat” on January 27, 1648. With this decision, painting and sculpture were declared to belong to the “liberal arts” and so removed from the control of the guild system”…

…”From then on they were not in the category of cabinets and armors, but in the same category as astronomy, music, arithmetic or grammar. Those were all “non-material” and individually conducted activities, not possible to be organized in the guilds, and thus couldn’t have manufacturing standards. Now painting became the result of a rather reflective activity similar to poetry, and not something that is valued because of the mastery of the hand, and so introducing the concept of a “learned artist” instead of an “ignorant artisan”…

…”For a while the effects of this decision were not felt, and for decades members of the Academy diligently followed the high quality craftsmanship standards. However, through the non-commercial “beaux art” scene established around the annual Salons initiated by Minister Colbert, the emphasis on the rigid quality of the painting gradually loosen, but the high craftsmanship standards maintained throughout the XVIII century, before and continuing after the Revolution. However, by the beginning of the XIX century, some artists like Delacroix had pointed to the direction which was later picked up by Impressionists (Monet) and Post-Impressionists (Cezanne) and the road became open for Picasso, and from there to Malevich and Duchamp. It is very hard to imagine how these works could have ever emerged from any painter or sculpture guild system.”…

…”From the time of the Louis XIV State Council decision, painting and sculpture as hand crafts were gradually transformed into an intellectual, reflective in a way philosophical activity that happened to be expressed non-verbally establishing a context within which even a “found object” named ready-made could become art. We could also notice a certain parallel between a urinal brought by Duchamp into an art exhibition becoming “The Fountain”, and a broken statue of a half naked young man brought into the Belvedere garden that became “Apollo Belvedere”. In both cases a previously existing object was taken from one context and placed into another where it acquired a new meaning, becoming an art object. Both had a previously defined purpose, why they were produced: a urinal to be installed in some public toilet, and a statue of a young man likely to be placed in some public temple or square”…

…”In addition to the Art History and Art Exhibitions, an important institution that defined what we call the art scene is the Art Museum. The origin of the Art Museum could be traced to the already mentioned “Belvedere Romanum”, a collection of statues brought together primarily because of their beauty and exhibited in the Vatican garden. As I said earlier, we could consider statues like Tiber, Nile, Torso, Cleopatra, Apollo and Laocoon to be the first works of art. This was by no means the only collection of ancient statues at that time, but it seems that it was the most influential in directly or indirectly shaping the entire art scene. It became the core of the XVIII century museum Pio-Clementino, and was even briefly incorporated in the Musee Napoleon (Louvre), in the early XIX century. It can be seen today as a tourist attraction at the Vatican Museum”…

…”Another source for the museums were collections of curiosities that appeared in the XVI century, displaying various unusual objects both natural and man made, as well as collections of paintings like the Ufizzi. It was the Louvre as an art museum that brought together collections of statues and paintings into one coherent narrative and open to the public after the Revolution. It also included some of the objects from the French past removed from public places during the Revolution but salvaged by Alexandre Lenoir and placed first in the Museum of Monuments”….

…”During the Napoleon wars many of the treasures were taken from occupied European cities, including Belvedere statues and brought to the Louvre. The architect of this enterprise was Vivant Denon, an erudite, art connoisseur who was usually among the first to enter the city with a list of valuable works of art. He would find and confiscate them, pack and ship them to Louvre, thus becoming known as “The Packer”. It was Denon that was appointed by the Emperor to become the first Superintendent of the Musee Napoleon. With all this treasure in his hands, stretching throughout centuries and civilizations now assembled in one place perhaps for the first time ever, Denon had to consider how to display it to the public and what kind of objective rules to implement. After some thought he decided that all works would be exhibited chronologically and by national schools. These rules became standard not only for all the museums that appeared in the XIX century, but for the structuring of the Art History narrative as well. On the other hand, art museums became in fact Kunsthistorisches (Art History) museums. All the artifacts produced previously for some other purpose, now included in the museum’s collection, acquiring a new meaning, became works of art. Thus, those artifacts, like the paintings by Tintoretto, brought in the museum would have two layers of meaning: one deriving from the religious “The New Testament”, another from the secular “History of Art”. Although the Art History intended to be an objective story about the past, the entire past became in a way colonized by history. Later, artifacts from other cultures were incorporated into the museums, first in the ethnographic collections and subsequently in the art museums, thus becoming works of art as well. And the museums as a materialized art history became instruments in this colonization. That was also the moment when notions like “work of art”, “artist” and the very notion of “art” were being finally shaped. From that moment on, artifacts produced within the field of the art museum were intended to “play roles” only in the story called Art History, and as such could have only one meaning – that of works of art. In a way we should consider only these artifacts that appeared after the art museums to be the genuine works of art”…

(Excerpt from the Walter Benjamin’s lecture “The Unmaking of Art”)

Exhibition A Museum That is Not, Times Museum, Guangzhou 2011

A Museum That is Not

Text and Curated by:Nikita,Yingqian Cai

It all begins with two inquiries about this very specific “museum”.

When I first started to receive magazines and publications in the office, I always got phone calls from the couriers asking the same question every time, “Where is your…museum?” My answer usually includes designating referential object of our locality “Do you see the bank? Yes, the green one. Great! Right beside it.” The next day we opened the museum, I got a phone call on the way to work. In the middle of the noisy, crowded and hasty metro, I picked up a fragmented sentence: “Paintings…touched…” It was not the first exhibition in the recent history of China which presents a selection of oil on canvases and some sculptures by a group of established artists, but it was certainly the first real art exhibition in this neighborhood which located in the northern peripheral of Guangzhou. So what makes a museum less recognizable than a bank? And what makes a painting tactually more attractive than a flashing TV set in a store?

The above curiosities are not the only ones I re-learnt by working as a curator in a brand new museum in China. They just opened up a cluster of undefined motifs. If we are to approach the museum with an unknown manner attention to empirical encounters is crucial. It is simply judgmental to ascribe it to ignorance and the uninformed context. Reinvestigation is called for both the origins of these motifs and their incarnations on the level of institutional practice and public awareness. To carry on these inquiries and reinvestigation in the form of an exhibition together with series of events, and to try and manifest these undefined motifs, is exactly the starting point of this reflective journey of A Museum That is Not.

When it was still “the cabinet of curiosities”, owners and spectators of this proto-museum were obsessed with and fascinated by the exotic objects possessed by other human beings and their alternative way of existence. Museums used to be, maybe still are symbols of our omnipresent fetishism as well as capsules of the physical, spiritual and creative adventures that had been taken by the courageous, the talented and the autonomous. While Patrick D. Flores was commenting on the curatorial turn in Southeast Asia in one of his essays, he stated that “the autonomy of art that was presupposed as a basis of the avant-garde in the metropolitan West may not have been achieved”.

There are no longer any “new land” and “new human beings” for them to sampling so that the adventures of the bourgeoisie and their representatives are not only belated but also never fully realized. But the imagination of an adventure might be more exciting than the real adventure itself. My personal experience of visiting museums hadn’t started until I was twenty, it should be safe to claim it a common situation for educated Chinese who belong approximately to the same generation of mine. We barely have any collective memories of museums and visual arts, neither the idea of a museum as a trophy sanctum or a representative body.

Museums and institutions are running after illusionary projections of the so-call “emergence of the middle class” in some major developed cities. Visions of emancipation and education are foremost filtered by the market, the media, populism and ideology, then mediated by the artists, the curators, the institutions and the audience. It is not an oscillatory trajectory that has reached its peak and now being threatened by its decline, but a magnet nexus that keeps attracting random subjects and objects from around and collapsing into oneself.

Is it really such a bad thing that we don’t know what we want to be, but only what we don’t want to be?

A Museum That is Not is a title quoted from an essay written by Elena Filipovic and first appeared in the exhibition catalogue Marcel Duchamp: A Work that is not a work “of art”, maybe it is about a work that is not a work of art, and maybe it is about the legacy of modernism and it sounds a bit like a déjà vu institutional critique. Albeit none of these make much sense in this site-specific museum where the direct references are not the far away and abstract art system, but the bank next door, the TVs in a shop, the residential building it situates and the restaurants across the street. In reality, it is simply a deferred museum, so a deferred statement based on this deferred museum may be subversive. It is not even “A Museum That is Not”, but a performative statement about any other museums that are not and will never be. Answers that are doomed to fail the questions are expected to reveal new discoveries and point out new frontiers.

The idea of an adventure is hereby brought back to recreate a series of unexpected encounters. The state of (not) a museum in relation to some of its elicited reflections are opened up for exploration by the public, through various situations such as a museum that is completely dematerialized and performative (Hu Xiangqian, Xianqian Museum); a Museum of Unknown which will pose question as “What are we talking about when we talk about arts?”; a juxtaposition of a Museum of Modern Art (Museum of American Art, Berlin) that turned up from nowhere and an empty contemporary museum that manifests only an agreement between a curator and an artist, including but not limited to a letter, a bench, a painting, a conversation, a happy birthday song and a suspended promise of gaze (Liu Ding, Agreement); last but not least, a silent discotheque that should not be there, like a black hole in the end of a story that proves our expectations all futile (Wilfredo Prieto, Mute).

For seven full weeks, guided tour of the pre-exhibition, artist talks reaching out for university campuses, lectures by a suspiciously deceased museum director, film screenings and tea party about museums, workshop on how to make one’s own newsletters and a half-day exhibition in a nearby residential apartment will prop up frequently, persistently inviting the public to revisit the museum and step out, then turn their backs to it and forget all the craps about a museum with a few unresolved questions till the next time. To eradicate the delusion of a coherent story-teller, descriptive and fictional narratives are chosen in stead of explanatory statements. Inside the accompanied brochure of the project, imaginary illustrations are presented rather than images of the actual works. In the space, no unified labels with information of the materials, the year and the artist will be applied. Booklet, signs, paper, titles and text would be found scattered throughout the exhibition. By calling all the invited participants “contributors”, the border between art and non-art are to be shifted and explored.

Let’s go back to the inquiries about the bank and the paintings being touched. The usual way to answer them is to defend “why a museum is so fundamentally different from a bank” and emphasize on “why a painting should never be touched”. But if we are talking about a tradition we never really owned and an obsession that we don’t really care, who are we defending for and against?

Exhibition Ai We We is in China, Berlin 11.11.11

Exhibition Museum of Immortality – Ashkal Alwan Beirut 2014

Exhibition A Story of Two Museums – James Gallery, CUNY New York 2014